Data brokers collect and aggregate your personal information from apps, websites, public records, credit reports, and more. They then share and sell this data to almost anyone they choose, often with little oversight, earning billions of dollars each year.

This can lead to the abuse of your personal information. For example, governments can buy data they’d otherwise need a warrant to get.

If you live in the US and would prefer not to have data collected and stored like this, it’s up to you to figure out who has it and how to opt out (when opting out is even possible).

Meanwhile, data brokers face few barriers. In many jurisdictions, they analyze, share, and resell your information to companies, advertisers, and even governments, with scant regulation and no obligation to notify you. As AI-driven ad personalization is being developed, the value of your personal data has never been higher — and neither has the risk you’re facing.

In 2024, the data broker market was worth about $270 billion(new window), and it’s expected to exceed $470 billion by 2032. Some of the largest players, like Acxiom, Equifax, and Experian, have data on hundreds of millions of people and make billions of dollars each year(new window) selling access to their databases.

It’s a huge and scattered industry, with as many as 5,000 companies collecting and selling data worldwide. While there has been some pushback, with the implementation of laws like the GDPR(new window) in Europe and the California Consumer Privacy Act, enforcement is still patchy.

With that much money on the table and so many players involved, it’s almost certain that your personal data has already been collected, which could lead to identity theft, financial fraud, or you being denied credit, housing, or insurance.

- What are data brokers?

- What do they collect?

- Where do they get their data?

- Data brokers reduce your life to data points

- How does your brokered data shape decisions about you?

- Is data brokering legal?

- Which are the major data broker companies?

- How to stop this data collection

- Frequently asked questions

What are data brokers?

Data brokers (or information brokers) are companies or individuals that collect, process, and sell or share personal information about people — often without their direct knowledge, consent, or compensation.

They gather data from various sources, such as public records (like property ownership and court documents), online activity (web tracking, cookies, social media scraping), retail and loyalty programs, mobile apps and location data, credit reporting, and financial institutions.

Once collected, this data is compiled into detailed profiles and sold to third parties such as advertisers (for targeted ads), insurance companies (for risk assessment), employers (for background checks), law enforcement (for criminal investigations in some jurisdictions), and even political campaigns (for voter targeting).

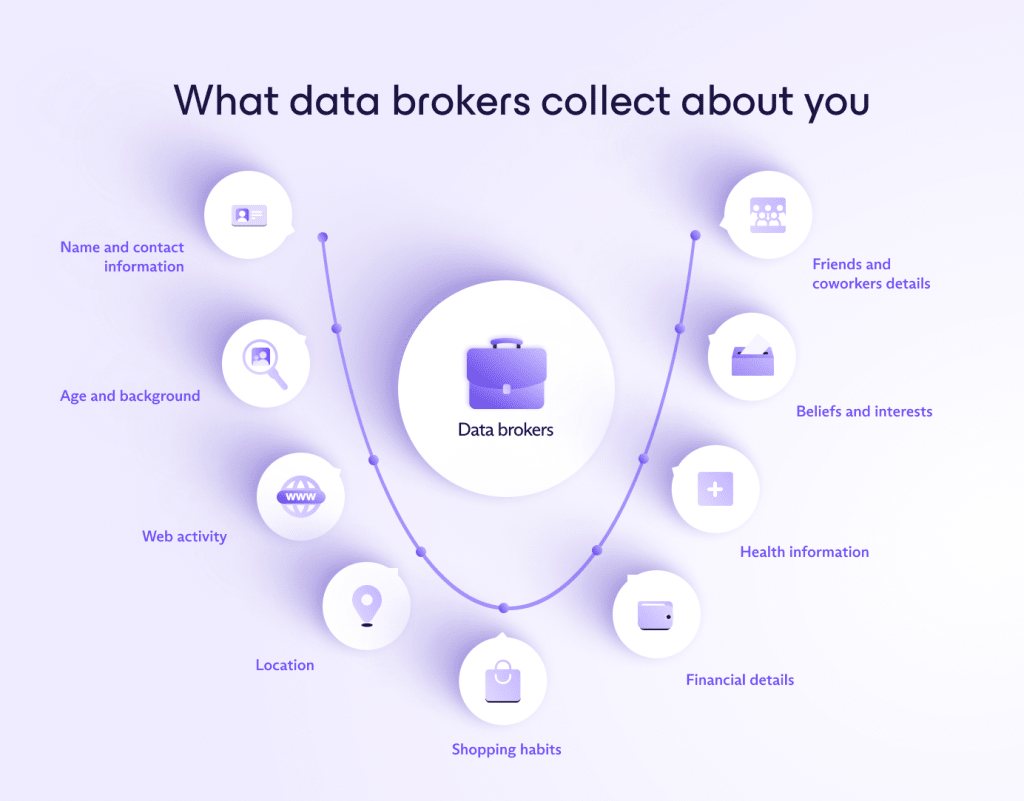

What do data brokers collect?

If a behavior or preference can be quantified, odds are there is a data broker monitoring that data and selling it. However, the most commonly collected data includes:

- Identity and contact information, such as your full name, aliases, date of birth, phone numbers, email addresses, past addresses, and Social Security number.

- Demographics, such as your gender, age, ethnicity, marital status, education, occupation, and income.

- Online behavior, such as visited websites, search history, clicked ads, social media activity, online purchases, and newsletter sign-ups.

- Location data, based on your GPS, WiFi, Bluetooth, app data, and geotagged photos.

- Purchasing habits, such as your shopping behavior, brand preferences, loyalty cards, subscriptions, and anonymized credit card use.

- Financial profiles based on your credit score, loans, mortgages, property ownership, and public financial records like bankruptcies or liens.

- Health signals based on fitness tracker data, health-related searches, pharmacy purchases, and potential medical conditions.

- Lifestyle and beliefs, such as hobbies, political leanings, religious affiliation, personality traits, and media habits.

- Social and professional connections, such as household members, relatives, friends, co-workers, and employment history.

Read more: Your address is out there — and it’s not hard to find

Where do data brokers get their data?

In the age of surveillance capitalism, a sophisticated ecosystem of data trackers has developed, and nearly all of them eventually feed into data brokers’ databases. This list includes:

- Public records and government sources, such as court filings, property deeds, voter registrations, and marriage licenses.

- Retail and commercial data, such as purchase history, loyalty programs, warranty cards, and catalog sign-ups.

- Online tracking, as websites and apps may use cookies, pixels, and trackers to record your browsing, clicks, and activity.

- Social media, such as public posts, likes, followers, and check-ins.

- Apps and services that sell or share user data with brokers — often quietly and buried through terms of service.

- Data held by credit bureaus, such as credit reports and financial activity, may be shared under certain conditions with brokers, particularly in the US.

- Surveys and sweepstakes, where people voluntarily disclose their personal information.

- Location data collected by apps that ask for GPS access (like weather or fitness apps) then sold as anonymized movement patterns.

Data brokers reduce your life to data points — here’s how

Data brokers thrive because there are countless organizations willing to pay top dollar for your data. This information can be used for nearly anything, from targeting ads to tracking down suspects. Some of the most popular customers and use cases include:

- Businesses buy detailed consumer profiles — such as “new parents in urban area” or “tech-savvy homeowners” — for targeted ads, customer acquisition, and retention.

- Insurance companies use brokered data to assess your risk and set premiums, often based on inferred behaviors like health risks or driving habits.

- Lenders can use brokered data for alternative credit scoring by relying on information like shopping habits or bill payment history when traditional credit reports fall short.

- Political campaigns may buy voter data to tailor messages based on your views, past donations, or issues more likely to concern you. For instance, suburban voters concerned about education funding may be targeted with school-focused ads.

- Some brokers run or feed data into websites that let anyone look up people’s names, addresses, relatives, and phone numbers.

- Governments or law enforcement agencies may buy data(new window), such as location or financial data, rather than request it with a warrant.

- Data brokers may trade data with one another to enrich their databases and expand their reach into new industries and regions.

How does your brokered data shape decisions about you?

The impact this data trade can have is far-reaching, often hidden from public view, and deeply personal. They collect and monetize information that may not seem significant on its own — like the apps you use or the stores you frequent.

But these fragments can be combined to create a surprisingly detailed portrait of your life, including routines, preferences, financial standing, and vulnerabilities. While some of this data isn’t directly tied to your name, it’s often linked to persistent identifiers (like your IP address(new window) or browser fingerprint), making it easy to re-identify(new window) you without ever showing your face.

Once your personal data is exposed and centralized, it can be traded endlessly — with little chance of you regaining control. And while you may never have knowingly agreed to it, you could become a target for cyberattacks if the company holding your data is breached, potentially leading to identity theft, fraud, or even stalking.

Beyond privacy and security risks, the lack of transparency is just as troubling. People rarely know what’s collected about them or how it’s used, and attempts to delete data are often complex by design.

Worse still, these detailed profiles can be used to influence decisions that shape your life, beyond personalized ads or targeted political messaging. They can manipulate behavior, amplify misinformation, and silently reinforce bias, exclusion, or discrimination.

Is data brokering legal?

The business of collecting, packaging, and selling people’s personal information is generally legal, depending on the country. In the US, for example, there’s no federal law that regulates data brokerage, but California, Vermont, Oregon, and Texas require data brokers to register(new window) and give people ways to opt out. EU citizens are protected under the GDPR, where companies must have a legal basis to collect and share personal data.

Despite these legal protections, recent investigations into state data brokers have revealed major flaws in the system. Many companies fail to register everywhere they should, a large share either never respond to lawful deletion requests or demand even more sensitive personal details first, and some deliberately hide their “delete my data” pages from Google.

In the California Data Broker Registry, for instance, 35 of the 499 registered companies had added noindex code to their opt-out or data deletion pages, making them undiscoverable on search engines like Google or Bing, and five had no opt-out page at all.

Which are the major data broker companies?

Several massive companies dominate the $270 billion data broker industry, with Acxiom, Experian, Equifax, among the biggest players. Here’s what you should know about them:

Acxiom

Acxiom is one of the world’s largest data brokers, operating in 36 countries and processing 1.2 trillion records a month — much of it collected directly from people. It claims to have data on 2.6 billion individuals, each profiled using over 10,000 traits.

Experian

Experian is a global data broker and credit reporting giant, active in 32 countries with over 200 million users and 150,000 business clients. It has 5,000 data points and 2,400 audience segments.

Equifax

Equifax is a global credit-reporting powerhouse and a major data broker that operates in 24 countries. With nearly $5 billion in annual revenue, the company aggregates data on over 800 million individuals and 88 million businesses worldwide.

How can you stop data brokers from collecting your information?

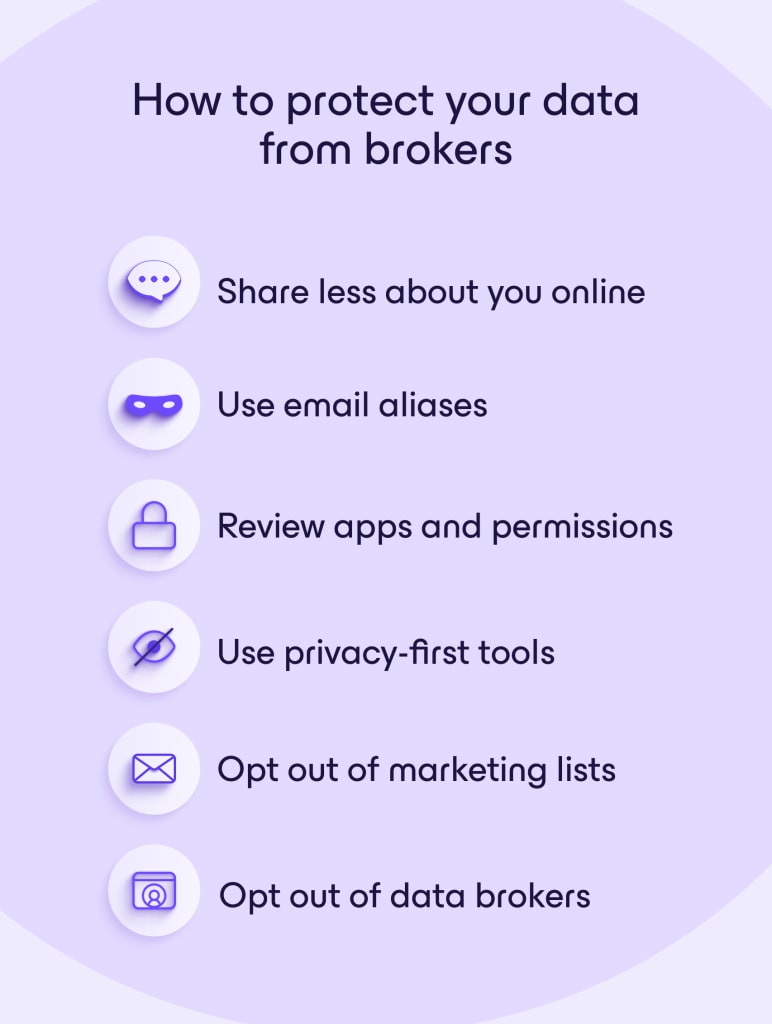

You can’t completely stop data collection by brokers, but you can reduce it. Here’s how:

- Limit what you share, avoid giving real details like your full name or actual birthdate when signing up for services, and think twice before filling out quizzes, surveys, or sweepstakes forms.

- When subscribing to online services, use email aliases that forward messages to your main inbox. This protects your real email address, lets you identify who shared or leaked the alias, and allows you to easily disable or delete the alias if you start getting spam.

- Remove yourself from marketing lists by unsubscribing from newsletters, catalogs, and promotional emails you don’t use. In Proton Mail, you can easily do this in the Newsletters view.

- Review your mobile apps, remove the ones you don’t use, and deny location access and tracking permissions for apps that don’t need them.

- Use privacy-first tools every time you go online, including browsers and search engines with tracker blockers, a VPN(new window) to mask your IP and encrypt your traffic, secure cloud storage that doesn’t scan your data, and encrypted email for safe communications.

- Opt out of data broker sites such as Acxiom(new window) and Experian(new window) and look yourself up and request removal from people-search websites. You can also use services like DeleteMe or Privacy Bee, which submit opt-out requests on your behalf across many websites, although they’re not always effective(new window).

You can take steps to reduce your exposure — every bit helps. But ultimately, the only real way to stop data brokers from collecting, exploiting, and selling data is through strong, enforceable regulation.

Until that happens, tools that put you in control of your data are your best defense.

Frequently asked questions

Can an information broker create shadow profiles even if I avoid social media?

Even if you try to limit your online activity, an information broker can still build profiles about you. These companies pull from offline sources like property deeds, DMV records, census data, and even information shared by others in your household or workplace. For example, if a friend lists you as an emergency contact or tags you in a photo, that data can be connected to you.

Do data brokers use AI to analyze and expand their datasets?

Many brokers use artificial intelligence and machine learning to collect information and make assumptions about your lifestyle that you may never see or have the chance to collect. For example, Publicis — the world’s largest advertising company, which also acts as a data broker — has built CoreAI, a platform it says can profile over 2.3 billion individuals. Details such as household spending habits and family preferences are used to decide whether someone should be targeted with budget products or high-end offerings.

Can you make money from your own data instead of letting brokers sell it?

Although the idea of personal data monetization is still in its early stages and nowhere near competing with the massive data brokering industry, it’s beginning to spark interest. A handful of platforms already let people opt in and get rewarded, such as apps that pay users directly for sharing browsing activity or shopping receipts.

Others, such as Datapods, let users license their data in packages, decide exactly what to share, revoke consent anytime, and earn a portion of the revenue. On a national scale, Brazil’s dWallet initiative offers citizens a “data savings account” to securely store personal information and sell access to it on a per-offer basis.