When securing a system or your online accounts, setting a strong password is the most important thing you can do. But what’s stronger — a password of apparently random characters or a passphrase of several unrelated words?

This article explains which you should use and when. To start, though, let’s look at what a passphrase is.

- What does passphrase mean?

- The memory problem

- Adding randomness

- Passphrase vs. password: which should you use?

What does passphrase mean?

When you identify yourself to get access to an online account or file, you usually use a password of some kind. You could also opt to use a passphrase. A passphrase is a sequence of four or more words, with each word in the phrase having four or more letters. Spaces aren’t necessary, so you can have a passphrase that looks like table chair book candle or tablechairbookcandle.

In function, passphrases are the same as passwords, but they differ in important ways. The first and most obvious difference is length. While passwords should be at least 15 characters long, passphrases, by their nature, are usually going to be at least 20 characters.

This is a massive advantage. Password entropy — the measure of a password’s difficulty — increases with length. Though longer doesn’t necessarily mean more secure, something we’ll talk about more in a bit, using a passphrase is one easy way to make a password stronger without too much hassle.

Despite being longer, though, passphrases are much easier to remember. For example, the table chair book candle passphrase from before is a simple mnemonic device, a way to recall memories. You sit at the table on a chair reading a book by the light of a candle. Though it’s a lot longer than the average password, it’s a lot easier to remember.

The memory problem

Passphrases solve a huge disadvantage of passwords, which are hard to recall if they’re even remotely secure. While a short word (like your pet’s name and the year you were born) can be easy to keep in mind, it’s also extremely easy to crack through dictionary attacks(nieuw venster), where the attacker’s software “guesses” your password by running through known combinations of words.

To fix this issue you need to add special characters to passwords, which is why online platforms often ask you to add numbers and special characters when creating your account. By adding numbers, capitalized letters, and special characters, you’re misdirecting dictionary attacks, and the more random-seeming you make a password, the harder it is to guess.

For example, if you decide to use the word aardvark as your password, you’d have to make it harder to guess by adding numbers, maybe replacing the A’s with the number four, so 44rdv4rk. To add some randomness, you might want to spare the first A that treatment, and maybe make it a capital, for good measure, turning it into A4rdv4rk. Then, add some symbols to make it really weird, so you end up with #A4rdv@rk!

This all looks good, and adds some nice randomness to the word, but you’ve just made the issue not one of security, but of memory. If you sign up now, forget about that account and then try to sign in a month or two later, you’re going to struggle to remember which letters you substituted and how. (Writing passwords in a notebook is not usually a good idea for many reasons.)

While your brain likely remembers “aardvark” just fine, all the other stuff is just too random to remember correctly. Plus, since you should never reuse passwords, this is just one of dozens you’ll need to recall.

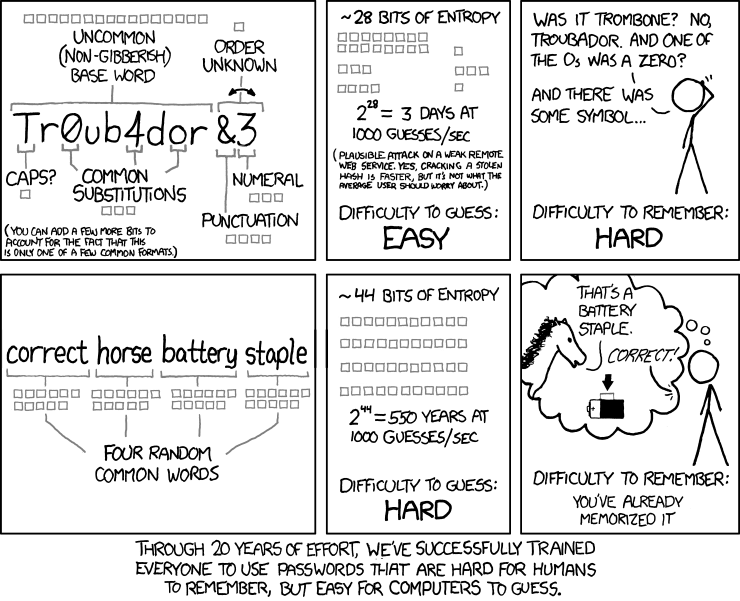

This tension between security and memory was best summarized by cartoonist Randall Munroe, author of the science-themed cartoon XKCD(nieuw venster):

It seems clear, then, that passphrases are better than passwords. However, this argument relies heavily on human memory as a premise. Let’s see what happens if we take that out of the equation.

Adding randomness

Passphrases are easier to remember and, by virtue of being longer (i.e., having more entropy), are more secure than short passwords. However, that isn’t the whole story. As we discussed, the weak link is human memory; what if we replaced it with a computer’s memory?

Enter password managers, programs that store passwords for you and autofill them wherever you need as you browse the internet. They make life a lot easier by autofilling passwords wherever you go, but, more importantly, they also add a lot of security by generating and remembering long, complex passwords for you.

For example, if you’re using our password manager, Proton Pass, any time you create a new account on a site, the Pass browser extension will offer to create and store the password for you. Where normally you’d do something like our “aardvark” from before or a combination of your hometown and birthday, Proton Pass’ password will be something like rZa;8g=6^P”kL*3 which is impossible to remember for most people.

This kind of password with over 15 characters will be practically impossible to crack through brute force attack, and you won’t need to remember it. As long as you have a password manager and use it to create long, complex passwords, the password vs. passphrase debate is irrelevant. Your account is secure.

But what about securing your password manager itself? A random password would be great but hard to remember. This is where a passphrase comes back into play: A passphrase like table chair book candle will work fine.

Passphrase vs. password: which should you use?

To summarize what we’ve covered: If you compare a passphrase to a truly random password, the password is the better, more secure option. The problem is human memory. The only way to remember a random password is to use a password manager of some kind, which you can protect in turn with a much easier-to-recall passphrase.

Of course, in this case you also need to make sure the password manager itself is secure, private, and easy to use. We developed Proton Pass with these goals in mind. It uses end-to-end encryption to keep your data safe and also benefits from Swiss privacy laws that make it easy to keep your private information private.

Besides that, it also comes with some more direct benefits, like two-factor authentication, which adds an extra authentication step in case your password is compromised in some way. (Remember, a good password protects against brute force attacks, not against phishing where an attacker tricks you into giving your password away.)

On top of that, Proton’s mission is to make your emails, files, passwords, and other data private by default. Your logins and personal email addresses in particular are part of your digital identity, which is worth protecting in the same way you protect your passport or ID numbers. Proton Pass offers hide-my-email aliases in addition to secure password storage to give you additional privacy.

If that sounds good to you, you can sign up for Proton Pass for free and join the fight for a better internet.